Monday, September 30, 2013

Is This Boring Or Are You Just Stupid?

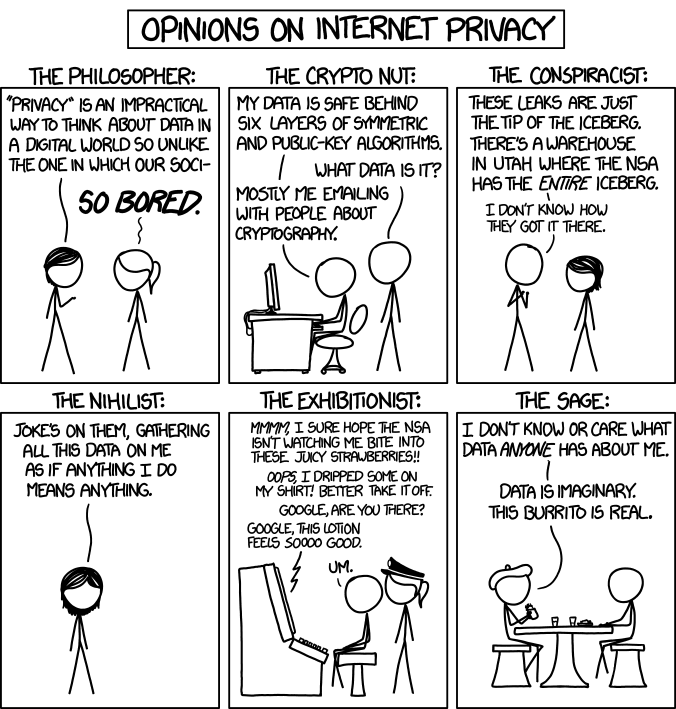

Last week the always-great XKCD ran a clever comic strip showing different opinions on data privacy. There is the exhibitionist, who intentionally puts X-rated personal stuff online hoping the NSA is tuning in. There's the nihilist, who is convinced their data means nothing, so who cares? And right there in the first panel there's the philosopher, who starts to opine about the differences between internet privacy and IRL privacy but stops there because the person listening thinks to herself, "SO BORED."

Of course, it's funny because it's true. Philosophy is boring. More importantly, it's frequently way more boring than it has to be. Various reasons, partly to do with the search for precision and making arguments and ... oh, sorry -- SO BORING. Let's just say there are various reasons and move on.

At the same time, can we just pause for a moment to acknowledge that the philosopher is the one person in the comic saying something serious, sensible, important and possibly true? And can we be honest and up front with one another about the fact that "so boring" is not a real criticism in the sense that "ignorant," "simple-minded," or even "mistaken" are?

I like to think about complicated things and then express those thoughts in speech and writing, so I'm on intimate terms with with the "SO BORING" critique. My students are bored by reading Mill's "Utilitarianism" and hearing me talk about it. Colleagues in other departments are bored by the endless distinctions and exception clauses that philosophers always make when they talk about anything. I've seen countless eyes glaze over when I try to explain that copyright and open access are complicated, because artists need to live on earnings from creations, whereas protections for scholarly research are very often a hindrance, and not a benefit, to scholars themselves ... yes, I know, compared to "information wants to be free" or "downloading is theft," this is such a BORING point of view.

I got news for you. Sometimes the truth is boring. Deal with it.

It's also worth nothing that boring is in the eye of the beholder. And while there are surely some boringness judgments that reflect genetics or your deep inner self or whatever, a huge part of why you do or do not find something boring has to do with your own habits, choices, and behaviors, which make you into the kind of person who is or isn't bored by something. This means, in some ways, you are responsible for your boredom.

It's not rocket science. If you spend a lot of your time watching action shows, playing video games, multitasking with Facebook and Twitter while you eat salty chips and cookies and text your friends, then settling down to read or just to learn about something slightly complicated is going to have the feeling of Herculean effort, like you're climbing the most boring mountain in the world. If you spend a lot of time doing things that are even mildly intellectually demanding, those things will not be boring.

Please note: I am not saying there is anything wrong with action shows, snacking, and texting! Those activities are all fine. The problem is when you do them all the time and don't do anything else, you make yourself stupid. And yes, you are doing it to yourself.

And here I think a harsh truth must be said: many people are turning themselves into the mental equivalents of toddlers with respect to what is and isn't boring. When they say something is "boring," it's not that it's boring, it's that those people have made themselves stupid.

I could go and on about the dangers of a world full of people who are really easily bored, but let me just point out one thing, which is that in addition to their other problems, people easily bored by thinking about things have the mental energy only for the most oversimplified and reductive view of things. So when the truth is boring, they cannot deal with it.

I got news for you, people. Often the truth is complicated. Often, simple slogans that sound like rallying cries -- "information wants to be free! downloading is theft!" -- are deeply mistaken. Often they're deeply mistaken because they're simple, and the truth isn't.

If you're the kind of person who uses the expression "TL;DR" to make fun of anything that goes on for more than a few sentences and doesn't contain the elements of some zany narrative, I got news for you: it's not boring, you're just stupid.

Monday, September 23, 2013

Dear New York Times: I Don't Even Know Who You Are Anymore

Yeah, I thought so. You know, you're really not fooling anybody.

In fact, some of your friends think you're going around the bend. They're disgusted at the way you still pretend to be doing journalism, as if you're asking the hard questions and challenging the status quo, when so often you seem to be just a mouthpiece for various power figures.

And I have to say, I've been wondering if you even know who you are anymore. It's like toadying has gone from being something-you-do-to-suck-up on occasion to being part of your core self. Do you even have a point of view? Is there any there there?

We see you around town and you're all "Hey, I'm a thoughtful guy!" When you poke your head in at the university you put on your Dockers and a T-shirt, as if to say, "I, too, might have been a professor! I just thought journalism would make more of an impact. We all want to change the world, right? Let's put our heads together!"

So when we see you out schmoozing with the Titans of Finance, we're like, WTF? What are we supposed to make of that? Your school-girl crush on Wall Street is obvious to everyone, and your evident desire to be an insider with the powers-that-be clique is cringe-inducing.

You do realize, right, that you can't be outside smoking pot with the cool kids and also be an anti-drug student council president type? Did you not see The Breakfast Club, or something?

I first started to notice this weird Zelig-like quality you have when I dipped into the Real Estate and Dining sections. Back in the day, I just read the news: I had my opinions, sometimes conflicting with yours, but I appreciated the way I could learn stuff from you.

When I branched out into the other sections, though, it was like finding out that your friend who hangs out with you drinking Two Buck Chuck and commiserating about student loan debt is secretly vacationing on a yacht with Beyoncé and didn't even tell you about it.

Suddenly, I realized you were shopping for million dollar apartments and gazillion dollar second homes. Even crazier, you never seem to eat at any normal affordable restaurants -- it's always some crazy place where a bottle of wine is a hundred dollars.

Then I started to notice it everywhere. In the Science section, you're talking about climate change, and in the Styles section you're talking about how it's fun to have 24 hour electric fountains or live in houses made all of glass or fly back and forth to Europe just for the weekend.

At a basic and practical level, I don't even get how it works. I mean, you guys are journalists, right? And you work for The New York Times? You can't be making all that much money. How is it that all the people you seem to know are hiring 24-hour nannies, competing for fancy private nursery schools, and "wearing Prada"?

I don't know what to say about our long-term prospects, New York Times, because I've been seeing someone else on the side. When you get your identity issues sorted out, give me a call, and we can talk.

Monday, September 16, 2013

Inequality And Well-Being: A Fable About The History Of "Efficiency"

|

| From Mother Jones |

Once upon a time there were some philosophers who came up with the radical idea that what mattered in life was bringing about the most happiness and pleasure possible, and the least pain and suffering. "Everyone counts for the same amount!" they said. "The greatest good for the greatest number!" You add it up. It was a moral requirement: always act so as to bring about the most pleasure for the least pain. They called this "utilitarianism."

Whatever your reservations about this view (and I have a few), you have to admit that it is a pretty radical idea.

Since a dollar given to a poor person will bring about a far greater increase in well-being than a dollar taken from a rich one will cause pain, there are immediate and deep egalitarian implications. Since animals feel pain and pleasure, they are immediately included in the moral calculus; since their factory farm life and death is worse for them than your hamburger pleasure is good for you, veganism for everybody. Since you have to take each person into consideration equally, you must foster the pleasures and ease the pains of strangers on the other side of the world equally to the pains and pleasures of your friends, your family, yourself. Since people can be mistaken about what is good for them, it's true well-being we must maximize, not just the satisfactions of, say, consumer items.

Status quo: demolished.

Back in the day, economists had the sensible idea that utilitarian concept of maximizing would be a good concept for evaluating policies, schemes, and social frameworks. One thing they noticed early on, though, was that measuring pleasure and happiness in an objective way is difficult. For this and other reasons, they shifted from measuring pleasure and happiness directly to measuring the satisfaction of personal preferences. Of course, preferences in the mind are also hard to measure. To address this, they started using the idea of "revealed preferences" -- which are preferences you reveal through your actions. When you buy some cargo pants, you are revealing a preference for cargo pants over the money and over other things you could have spent that money on.

I'm not sure exactly when the term "efficiency" came into use, but the idea was to maximize the satisfaction of revealed preferences at the least cost of frustrating them. As is often pointed out, there are immediate peculiar implications of a strategy of maximizing revealed preferences. In our ordinary lives we do not treat all preferences the same, as things to be fulfilled. A preference for cruelty, harm, or racial discrimination isn't the same as a preference for risotto. A problem gambler who loses his home "reveals a preference" whose satisfaction hardly seems to be maximizing his well-being.

And on top of all that: where do preferences come from? Efficiency as preference satisfaction doesn't concern itself with this question, but it's no secret that our preferences are deeply influenced by our cultural surroundings, our family and friends, and advertising. In a capitalist society like ours, there are armies of people working 'round the clock to instill in us preferences for cargo pants, Ford Probes, and giant television sets.

While there are still egalitarian implications -- the preference a dialysis patient has for a cure is stronger than anyone's preference for a new yacht -- maximizing revealed preference now says that for anyone who wants to buy cargo pants, Ford Probes, and giant television sets, maximizing well-being means delivering those things.

Status quo: altered.

Often these days, though, "efficiency" is measured not in terms of preference satisfaction, but in terms of maximizing goods and resources. A policy or social framework is efficient if it produces those things.

Bam! This immediately undercuts the egalitarian implications of efficiency. If we're counting dollars, the benefit to a poor person of getting or keeping a dollar is now equal to the cost to a rich person of losing, or losing out on one.

Indeed -- political rhetoric these days often invokes an idea opposite to that of moral utilitarianism, claiming that since a rich person might be a "job creator," efficiency requires preferring them as recipients of goods and resources (why increased assets, rather than increased demand, is thought to be the key issue, I've never understood). There are people who believe this benefits the poor indirectly, but the point here is that conceptually, it needn't whatsoever. Efficiency as maximizing goods and resources just counts the total. It doesn't track who is getting what. Increased efficiency is 100% compatible with poor people getting poorer.

You might think it couldn't get any worse, but in fact "efficiency" in economic and policy talk often refers to "Pareto efficiency," which means that no one can be made better off without making someone worse off. This just assumes some starting point and looks for improvements that come at no cost. As Wikipedia says, "Pareto efficiency is a minimal notion of efficiency and does not necessarily result in a socially desirable distribution of resources: it makes no statement about equality, or the overall well-being of a society."

Status quo: reified. Rich get richer; poor people can suck it.

I'm not claiming to have given a full history of this important concept, just to have connected the dots in what I think is an illuminating way. There's more in the economist Joan Robinson's brilliant 1962 book Economic Philosophy.

I'm always astonished to see things in the news where people are like "OMG inequality is rising, what could explain it??" as if equality were somehow a natural state of things and we'd need a special explanation for a rise inequality. This makes no sense to me. In a world with unequal starting points and reasoning processes that don't incorporate fairness or justice, never mind equality itself, how would it be any other way?

Monday, September 9, 2013

Likabilism

|

| This is, of course, real. |

You know about racism and sexism. But what about likabilism?

In our society, a lot comes down to just how likable you are. Almost all hiring and promotion takes into consideration some subjective factors -- things like "leadership skills," or "being a good communicator." It's no secret that if people like you they judge you to have these skills, and if they don't, they don't.

Of course, I am not saying that somehow likabilism displaces other -isms as if we're in a post-racial, post-feminist, post-whatever world. world. Obviously not. In fact it's the opposite. Likabilism functions as a conduit for other forms of discrimination. Or maybe money-laundering is a better metaphor. You can't express your racist and sexist and other discriminatory attitudes and judgements as such. But you can still say "Just doesn't have the leadership skills," or "isn't an effective communicator.

But likabilism expands on and overlaps with the traditional forms of discrimination. Because as long as there are these subjective judgments in evaluations, likability is going to be a huge factor in getting ahead.

I was reminded of this reading the incredible-along-so-many-dimensions NYT story about trying to combat gender disparities at the Harvard Business School. Astonishingly, subjectively measured "class participation" makes up "50 percent of each final mark." 50 percent! Obviously likability is going to influence whether you read someone's remark as challenging something in an interesting way or as not-being-a-team-player or whatever.

The article raises the important issue of social capital: the ways social networks have economic benefits. Not surprisingly, students are attuned to the ways the social experience of HBS would benefit them: for example, "if the professors liked you, students knew, they might advise and even back you." If you aren't living in a cave, you can imagine how that affects the women in school: they can't seem ambitious, and they can't seem non-ambitious. Quotes from the article:

"Judging from comments from male friends about other women ('She’s kind of hot, but she’s so assertive'), Ms. Navab feared that seeming too ambitious could hurt what she half-jokingly called her 'social cap,' referring to capitalization."Of course it's not just a gender issue. Anyone who doesn't look right, doesn't act right, or can't afford expensive outings can't become part of the in-group -- in this case, an in-group that will determine in real terms how well you do in your career.

"The men were not insensitive, they said; they just considered the discussion a poor investment of their carefully hoarded social capital."

OK maybe you're thinking, "Boo-hoo, people at Harvard Business School." But honestly, this is everywhere now. As I touched on in the previous post, everyone now has to present a certain kind of face to the world, through social networking and the internet, through positivity and team-playerism, and so on: Like me! Pick me! I'm the one for you, world!!

Likabilism functions as part of what Philip Mirowski calls the "entrepreneurial self": you have to market and brand yourself, and you have to develop exactly the "self" that an employer wants to hire -- not just at work, but with your whole personality. Various forces have come together to create a language and framework in which any ill-fit with the expectations of corporations is considered a personal failing, something you need to deal with. For example, Mirowski quotes a passage from Barbara Ehrenreich's description of a boot-camp for the unemployed: "It's all internal .. it's never about the external world... it's always between you and you."

So: what are you gonna do? I often feel like lurking behind discussions of these topics is an unspoken hope that somehow freedom -- of people to do as they please -- and fairness -- everyone getting what they deserve for their talents and efforts -- and equality -- OK, not equality, but not massive inequality either -- are somehow essentially in harmony. Like, if we could just get people to stop being racist and sexist and discriminatory in all the awful ways, you could have a society in which everyone does what they want, and everyone gets their just deserts, and no one is too badly off.

Some of the Harvard interventions seem to reflect a hope along these lines. Like, if we could just get things sorted out, things would all ... get sorted out.

But likabilism means the problems of exclusion and inequality are much deeper than this would suggest. If you let people do what they want, they're going to exclude the people they don't like, and include the ones they do. You can't legislate equality of social capital. So fairness and rough equality are not going to just happen.

My own view is that because these are different and conflicting values, you have to find a way not to let one of them run away with you. You can't legislate social capital, but you can legislate against too much inequality: there are lots of economic policies and institutions that will have equalizing effects. And you can legislate that no one be too badly off as well.

An approach like this won't allow for everyone doing what they want and it won't produce full justice of what people deserve either.

But it might not suck.

Monday, September 2, 2013

How Is It A Free Country, If All Your Options Suck?

|

| The infamous "McDonald's memo." |

I was drawing up the syllabus for my fall course on introduction to ethics and values, and I found myself wanting to confront a weird situation my students find themselves in: while in one sense we live in one of the freest places in the world, their path through life feels, to them, extremely constrained.

In some senses, North America in 2013 is a free place. You can, to a large extent, choose what you want to wear, what bands to listen to, what tattoo to get on your butt, and whether you want to get plastered this Saturday. You have a choice about whether or not to major in Engineering, whether or not to join Facebook, and how nice you want to be to your parents.

But as is well known, just because you have choices doesn't mean you're free. If someone holds a gun to your head and says "Your money or your life!" you're not being given a choice. You're being coerced. There are options, and you have to choose, but the latter option isn't an option in any meaningful sense.

By this same logic, it would seem that -- even if there's no robber -- if you make a choice for something you hate because the other options are worse, then in some sense you're not really free in making this choice. You have a low degree of a special kind of freedom I think of as "choice autonomy."

In certain ways, people today have way less choice autonomy than they did when I was young. When I was in my twenties, I worked for a while as a waitress and bookstore clerk, lived in cheap crappy apartments, and didn't have a car, TV or any other expensive stuff.

This was not a bad option. I had enough pocket money for breakfast out, and evenings in bars with friends. I took the bus. Because there were no cell phones and computers and internet, my not having those things was a non-issue. Sure, I had some annoying bosses, but for the most part I worked for small independent restaurants without vast corporate strategies and crap like that.

A life like this now is so much crappier. Of course part of that is economical: the fact that you can barely live on a waitress-like salary these days has a lot to do with relative incomes and rising inequality and so on.

But it's way more complicated than money, because changes in our society have made the life of the non-well-off much worse than they used to be in so many ways. Working a low-paying job now often means working for a giant corporation which has typically worked out in excruciating detail how to get what they want out of workers without considering -- even while benefiting from -- the conditions that make those workers' lives a pain in the ass.

Low-pay workers now often have to deal with unpredictable schedules, no guarantees of full-time work in a given week, absurd and ineffectual policies involving sales targets and quotas for foisting on the public stupid things they don't need. They often have to be on-call, so not only do they need a phone, they can't turn that phone off. Since employers check on social networking presence, and even regard non-presence as a red-flag, workers have to constantly curate their online persona. Naturally, they have to do all this with a huge smile, a friendly hello, and a team-player mentality. It's revolting.

Complex changes in society mean even living on moderate middle class salaries can be challenging. During the burst of the housing bubble there was this surreal situation of cheering for rising house prices and moaning about their falling. I get the reasons -- mortgages, debt, saving, blah blah blah. Still, wasn't it odd not to see anyone spare one thought for the people who might want to buy an affordable house? Or just rent a little apartment for some reasonable rate?

All of this means that even if you win the early life lottery of good parents and money that can fund your education and all that jazz, the crappiness of low-pay work means you pretty much have to choose to fight the zillion other people trying for the brass rings. You don't have much of a choice. Of course, if you didn't win that lottery, forget it. You'll have little access to any good options at all.

Because of these facts, there's a sense of freedom in which people have less freedom, because their choices are not free but rather constrained. This use of the concept is related, I think, to the idea of "positive liberty," but it's not quite the same: I'm not talking about enabling self-determination and realization. I'm talking about having to choose X because all the things that involve not-X are awful -- not because one person made them awful for you in a moment, the way the robber did -- but because the world you live in made them awful for complex interconnected reasons.

If I'm right about choice autonomy it's a concept that can apply to anything. But on Labor Day it seems particularly appropriate to point out implications for worker conditions. If those conditions suck, that's a problem not just for well-being, not just for collective welfare, but for freedom and autonomy as well.

You sometimes hear arguments against rules and regulation justified on grounds that they would be coercive, would unjustly decrease the freedom of people and institutions to do as they see fit. My proposal is that "freedom" cuts the other way as well: when some options are awful, the choice for alternatives also isn't really free.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)